This day the reptiles remained in campaign mode, with an "eek, the dastardly, nefarious Chinese are getting involved" headline setting the pace ...

Even worse the Wong had suggested another Voice might be right, guaranteeing a reptile frenzy ...

Over on the extreme far right, the reptiles decided to give the bouffant one, peddler of highly dubious, unethical and bullshit Compass polling a break ...

What dismal choices.

A defiant simpleton "here no conflict of interest" Simon was still holding out hope....

By Simon Benson

Political Editor

In contrast, ancient Troy adopted the preferred reptile posture these days, of a pox on both their houses ...

The Prime Minister and Opposition Leader are decent and honourable but where is the courage and vision in this campaign?

By Troy Bramston

Senior Writer

Having already voted, the pond must confess to personal bias. A sense of deep ennui.

Neither of them offered the slightest hint of an interesting read, and triple that for Dame Slap, still harping on, in her relentless way, about Linda ...

The NACC says a referral from Linda Reynolds is still ‘under consideration’ after 18 months.

By Janet Albrechtsen

Columnist

Fergeddit it.

Is it any wonder that the pond turned to the bromancer, deeply unnerved, agitated and unhappy?

It was only a three minute read, so the reptile official timer said, but what joy he provided, and on a timely topic too ...

Oh Canada, elbows up, dig them into the bromancer ... and for those not interested in clicking on the image to read the fine print...

The header: Liberal lessons from Canada’s election result, Trump intervention, Donald Trump saved the left-of-centre Canadian Liberal Party from certain defeat, just as he may have denied the Australian Liberal Party.

The caption for an incredibly reflexive snap: A person takes a photo in front of a Canada sign on election day in Ottawa. Picture: AFP

The mystical injunction, as deep as transubstantiation (more of that anon): This article contains features which are only available in the web version, Take me there

Oh okay, the pond stole the bromancer's opening flourish, as he slumped over keyboard in despair ...

Trump, and Trump alone, saved the left-of-centre Canadian Liberal Party from certain electoral defeat, just as he may have denied the Australian Liberal Party what once looked like a serious shot at power in our election in a few days’ time.

Alone? While watching CBC's live coverage, the pond noted that many of the pundits credited a morsel of the turnaround to Carney, the sort of solid central banker figure likely to send bromancer and Dame Groan types into a frenzy, but do go on ...

The Liberals got rid of their unpopular leader, Justin Trudeau – Canada’s Jacinda Ardern – and replaced him with the sober but deeply dull central banker Mark Carney. However, that’s not what changed the course of Canada’s election. Trump began a series of nearly unhinged attacks on Canada, imposing, then withdrawing, then reimposing completely unreasonable tariffs, and insultingly and repeatedly telling Canada – a free, prosperous, sovereign, independent nation and one of the longest continuous democracies in the world – that it had no viable future unless it joined the US as the 51st state.

How mortifying, though Wilcox thought it was more fingers than elbows up...

The reptiles also interrupted with a snap, Supporters of Mark Carney celebrate as results are announced. Picture: AFP

Oh the shameless fully red harridans, jubilant and cheering.

The bromancer was outraged ... the fully woke were on the march ...

Support for the Canadian Conservatives, who were never part of the Trump bandwagon and had always distanced themselves from the Trump approach, stayed relatively steady. But support for the Liberal Party – which had governed incompetently and ineffectively for a decade, identifying with every woke cause on the planet, imposing immense green costs on business and consumers, while seeing their economy slip ever further behind that of the US – soared.

Then the reptiles committed an unforgivable visual crime. They linked together the Cantaloupe Caligula and the Duttonator, two peas in a visual pod ... US President Donald Trump. Picture: AP, Peter Dutton.

No wonder the bromancer was unnerved and deeply unhappy, and the pond supped on his tears ...

Not only that, the damage Trump has wrought on Canada so far has been economic. Carney’s credentials as an economist, certainly compared with the identity politics and social policy obsessions of Trudeau, provided just enough sense of change within the ruling party to make Carney a plausible choice for voters wanting both reassurance and change.

The Liberals only narrowly out-polled the Conservatives. Both main parties scored in the low 40s, a high percentage for the two major parties in a diverse federation with strong regional identities.

Couldn't the reptiles at least slipped in a graphic, even if it meant borrowing from CBC?

Oh there was laughter and joy and much road runner amusement, as imagined by the infallible Pope (with a tip of the hat to the immortal Chuck) ...

Sorry, sorry, there was much deep, ineffable sadness... Strelmark founder Hilary Ford says the re-election of Mark Carney as Prime Minister is “sad for Canadians”. “Mark Carney, certainly as the head of the Bank of England, was actually no great force in terms of economic change, nor prosperity. “I actually think this is rather sad for Canadians.”

Who on earth is Hilary Ford, and why should the pond give a flying fuck? Is she the same person as Hilary Fordwich, sad founder of Strelmark LLC?

The reptiles and their captions, but the pond still didn't give a flying fuck, and moved back to sup more bromancer tears ...

It would be as if, in Australia, Labor, the teals and the Greens scored 57 per cent of the vote between them. However that was distributed among the parties, it would be a big win for the left.

Unlike Australia, Canada doesn’t have preferential voting, but uses a first past the post system. That favours the big parties and helps them win the lion’s share of seats. The Liberals will be much happier if they get a majority – at time of writing this was unclear – but would be happy enough with minority government if they fall just short.

The reptiles offered a snap of the loser, Canada's Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre and his wife Anaida wave to the crowd at the Conservative election party in Ottawa. Picture: AFP

A final sup at the font of bromancer sadness ...

The result demonstrates, for the moment at least, the false promise of the Trump victory for centre-right parties internationally. Trump provides poor centre-left governments an excuse, a distraction and a ready-made smear of their domestic opponents that, no matter what they say publicly, they really yearn to be like Trump.

Indeed, indeed, everyone wants to be a fascist authoritarian, everyone yearns to be a Cantaloupe Caligula.

Why it's the deepest wish of the bromancer, that's why he understands the impulse so well ...

Sorry for the interruption, now for a final sup and a dire warning, bromancer style ...

The ALP should be careful not to follow the Canadian Liberals too closely. Even if Ottawa and Washington are at loggerheads, Canada’s geographical position means it is effectively defended by the US military, no matter what. It even has a US outpost, Alaska, between it and Russia. Although the US is more significant economically to Canada than it is to Australia, we are far more reliant on American goodwill and sustained commitment for our security.

It’s impossible to know what Trump thinks he might achieve by telling Canada it must become part of the US. What he has got is a left-wing victory in Ottawa, and America’s closest neighbour, and one of its oldest allies, deeply hostile and resolutely determined to work against US leadership internationally.

Trump may pretend it’s all part of a cunning plan. Actually, it’s just unbelievably dumb.

Did the bromancer just call his kissing cousins at Faux Noise unbelievably dumb?

What an insult, how incredibly wrong.

Why they're totally, completely, fully believably dumb every day of the week.

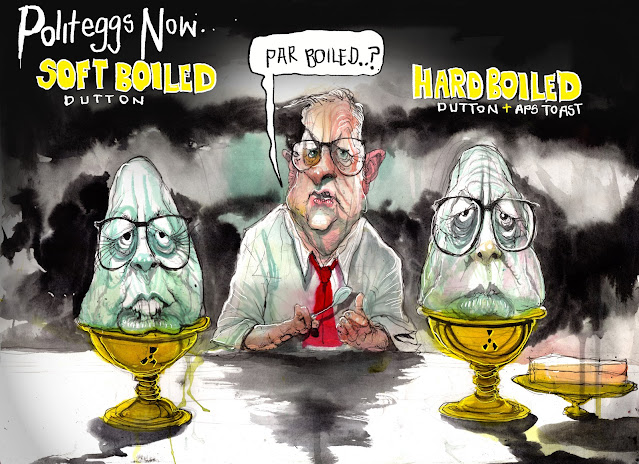

Time for a 'toon celebration with the immortal Rowe ...

And so to the bonus, and it's "Ned" nattering away as usual ...

Please, bear with him and the pond ...

The header: The flawed legacy of a pope of the people, Pope Francis was a pope of the people but he leaves a church challenged on many fronts

The caption: A College of Cardinals meeting have set a May 7 Conclave date to elect Pope Francis' successor. Picture: Mario Tama/Getty Images

The mystical incantation, up there with transubstantiation: This article contains features which are only available in the web version, Take me there

The pond imagines some of the reptile faithful are getting a bit restless and shuffling about in their pews, especially as the reptiles clocked this Everest climb at some five minutes.

But lordy, lordy, long absent lordy, this is the Catholic Boys' Daily ... this is the reptiles' daily bread and butter.

If you want to read clever dick stuff, head off to a place like McSweeney's for a short clever dick piece like This Five-Hundred-Word Bumper Sticker on My Tesla Explains Why I’m Not a Bad Person

This is where the rubber hits the road, this is where the gluten-filled wafer hits the coeliac throat, this is where the holy oil lands snap bang in the eye, this is where "Ned" does Conclave the Sequel ... but not before giving poor old Frank a hard time ...

The global response to his death testifies to a world in mourning for what humanity has lost. Wars rage in Africa, Europe and the Middle East, the bonds of co-operation are shattered within and between nations, and the march of science seems to both enhance yet threaten human nature.

At a time of complexity Francis offered the virtues of simplicity and faith. He led by example and his personal contact with people often changed their lives. His mission was a church dedicated to the poor, operating in the margins, his reference points being the wooden chair, the hostel room and the cross. Madoc Cairns, editor of Plough Quarterly, said: “Every act he takes is a gesture; images which illume truths; a hand pointing to somewhere past the limits of our sight.”

The reptiles interrupted with an AV distraction, featuring a host of devoted frock wearers, The Vatican has announced that the Papal Conclave to elect the next Pope will begin on May 7. The date was decided during a closed-door meeting of cardinals — the first since Pope Francis’s funeral over the weekend. A total of 135 cardinals will convene in the Sistine Chapel to vote on the next leader of the Catholic Church. The previous two conclaves, held in 2005 and 2013, lasted just two days.

The sight of so many frock wearers induced a fit of piety in "Ned" ...

Of the 135 cardinals eligible to participate in the conclave to elect the new pope, the geographical breakdown is: Europe 53, North America 16, Central America four, South America 17, Africa 18, Asia 23 and Oceania four. Jorge Mario Bergoglio reflected that universalism as the first Jesuit, the first Latin American and the first pope from the global south.

Francis came to downgrade doctrinal fixation in favour of evangelical outreach. He conceptualised the church as a “field hospital after a battle” – its task dealing with human beings was to heal wounds. “I dream of a church that is mother and shepherd,” Francis said. He put people before rules.

His papacy began by welcoming refugees on the remote island of Lampedusa; he urged priests to “get out of the sacristies”; he famously said: “If a person is gay and seeks God and has good will, who am I to judge him?” He encouraged different countries to realise their Catholicism within their own cultures, reflecting the challenge of a global church.

Shocking, what with the reptiles judging all the time, but there was also that Conclave thingie, surely worth a flutter, surely worth a fling, especially as the reptiles helped set the odds with a graph worthy of an ABC finance report ...

"Ned" had a hard time keeping up, and refused to give odds on the hot contenders. Instead he remained hot and bothered.

Lordy, lordy, long absent lordy, could the Popehave been a greenie Marxist?

Francis championed synodality – clerics and laity working together – yet the process rarely reached resolution. The story of his papacy is the challenge of holding a global church together as the tensions between progressives and conservatives intensified; witness his most celebrated encyclical, Laudato si’, a document with similarities to green Marxism.

Advocating “united global action” on the environment and climate, Francis aspired to reconcile the church’s historic tension between faith and science. “Doomsday predictions can no longer be met with irony or disdain,” he said. “For human beings to degrade the integrity of the Earth by causing changes in its climate” constituted “sins” – so people must engage in “ecological conversion” by changing the way they live.

Signalling scepticism towards Western capitalism, Francis said mankind must recognise the need for a “decrease in the pace of production and consumption” – that meant “the time has come to accept decreased growth in some parts of the world”. He repudiated the notion that global hunger and poverty will be resolved by “market growth” or higher profits, called for a Christian spirituality marked by “the capacity to be happy with little”, attacked the “absolute power” of finance and, reflecting the outlook of St Francis of Assisi, said “less is more”.

Eek, climate science ...

The reptiles had a different snap, featuring devoted frock wearer Frank, Pope Francis, looks out to the crowd from the central balcony of St Peter's Basilica after being elected 266th pontiff in 2013. Picture: AP /Luca Bruno

"Ned" was puzzled and alarmed ... frock wearing has that effect on reptiles ...

Having appointed Cardinal George Pell to reform Vatican finances – suffering from corruption and maladministration – Francis eventually gave up on the task. Pell later told me he worried that Francis could start issues but rarely finish them.

There seemed to be a divide between an Australian-based tradition of financial management and an Italian-orientated Vatican under a Latin American pope. The job is still not done. Pell speculated without knowing about the forces that led Pope Benedict to stand aside.

One of the most alarming Vatican policies is the 2018 formal compact between the Holy See and the Chinese Communist Party government – since renewed – over the appointment of bishops, with the former archbishop of Hong Kong, Cardinal Joseph Zen, warning such accommodation would “kill the church” in China. Zen denounced the agreement as a betrayal that gave “the flock into the mouths of wolves”.

Then came an AV distraction, Heavy is the white miter worn by the pope. Whoever emerges from the coming conclave as the new leader of the 1.4-billion-member Catholic Church will face a myriad of problems. Ciara Lee reports.

Heavy was "Ned", and solemn, and sad, as only the premium reptile pontificator can be ...

Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin is an apologist for Beijing who has played down religious persecution in China and is a candidate to replace Francis as pope. In 2021 he said “one cannot but be worried” about Australia’s nuclear submarine AUKUS agreement with the UK and US, prompting Pell at the time to defend AUKUS and say more collaboration was needed between democracies in Asia to balance the power of China.

RR Reno offered the remark that “if China becomes a Catholic nation in the next hundred years, Francis will have been vindicated in his tactics”. Surely correct.

The paradox of the Francis papacy is that much of the church’s growth in both the developed and developing world derives from the revival of Catholic tradition as opposed to its progressive concessions to Western secularism.

Bishop Barron said: “Francis had to have known that the church is flourishing precisely among its more conservative members. As the famously liberal church of Germany withers on the vine, the conservative, supernaturally orientated church of Nigeria is exploding in numbers. And in the West, the lively parts of the church are, without doubt, those that embrace a vibrant orthodoxy rather than accommodate the secularist culture.”

All this way and not a single joke about Pierbattista Pizzaballa, who has been amusing late night US comics all week?

Instead a snap of the man who actually killed the Pope stone dead in ten minutes, thereby providing even more material to late night comics, Cardinal Pietro Parolin welcoming US Vice President JD Vance at the Vatican earlier this month. Picture Vatican Media/AFP

Never mind, "Ned" spluttered out with a suggestion we all should come back in a hundred years, which the pond appreciated, but suspected might be a bit tricky achieving ...

He was a pope, a leader, and a common man with all the vulnerabilities that involved. He alarmed conservatives and he disappointed progressives – but perhaps such compromise is the only way to keep the church unified today. As his fellow Jesuit, Frank Brennan, said: “Certainty is the great enemy of unity. Our faith is a living thing precisely because it walks hand in hand with doubt.”

The legacy from Francis will be better grasped in another 100 years. But the response to his passing testifies to the power of tradition, the longing for moral leadership and the pulling power of ancient institutions whose purpose transcends the temporal world. These are the enduring verities that people want and seek – so contrary to the deluded popular culture that debases our times.

Oh yes, well said, as only a humbug working for the Murdochians, debasing the world with Faux Noise and the mango Mussolini, could manage without a shred of irony or self-awareness.

Speaking of the MM, the pond was delighted that the WSJ board had yet another moment of buyer's remorse.

There has been much useless blather about the first 100 days, as if that marker actually meant anything, but the pond found this effort enchanting ...

By

The Editorial Board (archive link).

What say the US reptiles of this gold bling addicted, bankruptcy loving tyrant?

There’s no denying his energy or ambition. Mr. Trump is pressing ahead on multiple fronts, and he has had some success. His expansion of U.S. energy production is proceeding well and is much needed after the Biden war on fossil fuels. He has ended the border crisis in short order.

He is also rolling back federal assaults on mainstream American values—such as by policing racial favoritism. Mr. Trump was elected to counter the excesses of the left on climate, culture and censorship, and he is doing it.

Even on popular causes, one problem has been needless excess. Harvard and other universities need to change, but trying to dictate their curriculum and faculty choices is an intrusion on free speech and risks defeat in court. His deportation of criminals is worthwhile, but denying due process and toying with the courts will sour the effort. The White House motto seems to be that if something is worth doing, it’s worth doing too much.

***

That’s especially true on tariffs, which could sink his Presidency. Mr. Trump was elected to control inflation and raise real incomes, but tariffs do the opposite. They guarantee at least a one-time increase in prices on imported goods that will flow through the economy. They portend shortages for consumers, and for businesses that source goods and components from abroad.

The tariffs are the largest economic policy shock since Richard Nixon blew up Bretton Woods in 1971, which unleashed inflation that Nixon tried to stop with wage and price controls and a tariff. The economic consequences arguably doomed Nixon’s second term, perhaps as much as Watergate.

It’s a mistake to think the tariff damage is only domestic. The willy-nilly assault on friends and foes has shaken global confidence in U.S. reliability. Ken Griffin, the investor and major donor to Mr. Trump, summed it up last week as a self-inflicted blow to the American brand. The U.S. is needlessly ceding global economic leadership.

China is already taking advantage by courting U.S. allies as a more dependable giant market. This will make it much harder to build a trade alliance to stop China’s often predatory economic behavior. Mr. Trump last week called us “China Loving,” which must amuse Beijing. Mr. Trump’s tariffs on allies are the real gift to Xi Jinping.

There are signs Mr. Trump is finally recognizing some of the tariff risks, as he now talks of doing some 200 trade deals. He is also saying he might unilaterally cut his 145% tariff on Chinese imports. We’d like nothing better than to see a retreat—a “Mitterrand moment,” as we wrote last week about the reversal by the 1980s French socialist. But Mr. Trump remains a long way from making such a pivot, and those trade deals won’t be easy to strike.

Mr. Trump’s second-term foreign policy so far is a work in progress. He is trying to reclaim Middle East sea lanes from the Houthis after Joe Biden’s timidity. And he is restoring “maximum pressure” on Iran to abandon its nuclear program. These are hopeful signs.

The main cause for alarm is his one-sided pursuit of peace in Ukraine. Until this weekend he had said scarcely a discouraging word about Vladimir Putin while squeezing Ukraine to make concessions that could doom it to future marauding. Much will hang on the details of an armistice, if there is one, and not merely for Europe’s future.

Joe Biden’s retreat from Afghanistan destroyed American deterrence. A debacle in Ukraine would do the same for Mr. Trump, with ramifications for Iran, North Korea and especially Chinese ambitions in the Pacific. Don’t be surprised if China decides to snatch Taiwan’s outer islands or tries a partial blockade. Mr. Trump told us in October that he’d respond to such a provocation with tariffs, but he’s already playing that card without success.

***

Voters re-elected Mr. Trump in part because they remembered fondly his first-term economy. But that success owed mainly to his pursuit of conventional GOP priorities like tax reform and deregulation. This term he is indulging his trade and foreign-policy obsessions, and the early results are negative. He’ll fail unless he heeds the warnings.

To heel, mango Mussolini, the reptiles are urging you to get around behind and to heel, and good luck with what you've unleashed, believably dumb Murdochians ...

And so back to Barraba and more of the Studebaker mob.

The pond only stumbled on this gathering by accident, and wasn't in the clan - after all the pond's first car had been a Ben Chifley model, a Holden FX...

What an array there was, and a few ring-ins too, and more on the morrow ...